By Alex Vipond

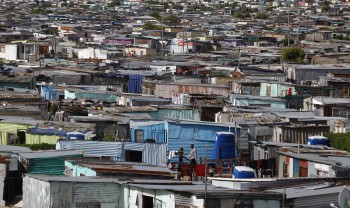

Driving east out of Cape Town, South Africa, you pass a sea of corrugated metal roofs that stretches out as far as the eye can see. Bright blue portable toilets and dull grey satellite dishes accent the rusty metal landscape.

Enterprising, poor South Africans on the side of the road sell food, cell phones, and so-called “starter packs”—everything you need to construct your own shack, the next metal drop in the sea.

These metal roofs are part of Khayelitsha, the largest township in the Western Cape. They have congealed into an informal settlement—a city of sorts, but one where the government does not track addresses, name streets, collect waste, install sanitation, or even take census. Development efforts have been going on for decades, but it is difficult not to imagine a glass ceiling hovering over the informal settlement, especially when the skyscrapers of Cape Town tower over the city less than thirty minutes away.

Sizwe Nzima has lived in Khayelitsha his whole life. His mom works in Johannesburg, South Africa’s largest city, and his dad lives in the Eastern Cape, so he lives with his grandparents. Growing up, school was one of the only reasons he ever left the township. At school, he got his first bite from the entrepreneurial bug.

“Back then, my school had just bought a vending machine. It was quite expensive – Fritos for 3 rand ($0.25), Doritos for 5 rand ($0.35). I knew these things were sold in Khayelitsha for 2.5 rand ($0.17), so I saved up until I could buy a box of Fritos, a box of Doritos, and muffins. Then, I came back to school…and stood next to the vending machine.”

After that, Sizwe’s slow-and-steady gains from formal education could never again compete with the allure of a cleverly earned profit. But he was determined to earn that profit from a more meaningful, sustainable source than an undercut vending machine full of junk food.

His first step was to identify a common problem that he knew extremely well.

“I grew up with my grandparents. One of the responsibilities I had as a kid was to go and collect their chronic medication. But when you enter a hospital, the first thing you’ll see is queues. You queue to get registered. You queue to get a folder. You queue to exchange your folder for a number. Then you finally use the number to queue up for your medications. There are queues everywhere!”

Next, Sizwe dreamed up the ideal solution: a delivery service that would bring medicine directly to the doorsteps of chronic patients. He imagined that this service would not only get medicine to patients faster; it would also allow the hospitals to focus on urgent and less predictable health issues. On top of that, all the other people like Sizwe, the Khayelitsha residents picking up medicine on behalf of a family member, would be free to spend their time more productively.

The more arduous part, though, was adapting the ideal solution to the real world. Sizwe started out alone, signing up customers and delivering medicine on foot for a small fee. He formed relationships with pharmacists who were at first concerned he was selling drugs on the street. He worked out the optimal routes in his head, noting where it might be necessary to taxi to the next client using the money he had already earned on the route.

He even expanded enough to hire help, opting to recruit ex-convicts, ex-gang members, and the homeless to help him deliver on bicycles.

“You see those guys sitting on the corner, and you probably think they’re just roaming around, waiting to rob people. But I figured that since they roam the streets, they know the address systems better than anyone else. So when two of them came to me asking for a job, saying they wanted to get away from their criminal record, I asked them one question: ‘Can you ride a bike?’ Now, they’re my two best riders. More than that, the community trusts them and sees them as good people.”

Satisfied with the service quality, people are now requesting doorstep delivery of other products, not just medicine.

Sizwe has realized that his medicine delivery service, originally a flight of fancy, is now becoming a full-fledged logistics company specifically for the poor, something that exists nowhere in the world due to the black box around informal settlement navigation. Without Google Maps coverage or government-recognized streets and addresses to lean on, companies like DHL and FedEx—giants of international logistics—are completely stymied.

Sizwe and his previously disadvantaged employees, on the other hand, are working with public health officials to expand Iyeza Express to all of South Africa, backed in part by a grant from NU’s Social Enterprise Institute.

—

Elaborate cursive script decorates the side of a bridge, one of the few that connect Khayelitsha to the outside world. It reads, “The People Shall Share in the Country’s Wealth.”

Framed by its corrugated metal background, the phrase is ironic, to say the least, and perhaps also a bit misguided—if Sizwe’s story has any larger lesson to impart, it’s that the people living in informal settlements may not need to share in South Africa’s wealth. Inside their communities, and inside all communities, there is plenty of wealth waiting to be created.

Maybe that wealth needs to be coaxed out by investors. Maybe it needs to be shielded from gang violence or political unrest. Maybe it needs access to a transportation network. But unless it is acknowledged, sought, and curated, a glass ceiling will continue to hover over those starter pack shacks.

As they ride around delivering health, entertainment, and opportunity to a community they’ve known their whole lives, Sizwe and his employees find wealth above and beyond cold, hard cash.

They are breaking through the glass ceiling, building up their metal roofs, and planning to take the rest of their community with them.